Jim Crow and the Green Book hotels

By Rick Holmes

Feb. 15, 2019

Orlando, Fla. – Division Street runs north and south, parallel to Interstate 4, and there’s a reason they named it that. In the bad old days, it divided Parramore – a neighborhood built in the 1880s under Mayor James Parramore “to house the blacks employed in the households of white Orlandoans” – from the white precincts to the east.

Black Orlandoans were told not to be caught east of Division after sundown.

Black Orlandoans needed medical care, and in the Jim Crow South, white doctors wouldn’t see them and white hospitals wouldn’t admit them. So when Dr. William Monroe Wells moved from Georgia to Orlando in 1917, he found a ready clientele. Dr. Wells built a house and medical office just steps off of Division, then built something that helped make his neighborhood a community: The South Street Casino had a basketball court and skating rink for young people who weren’t allowed into Orlando’s whites-only parks and recreation centers. By night it became a place where black musicians could perform for black audiences.

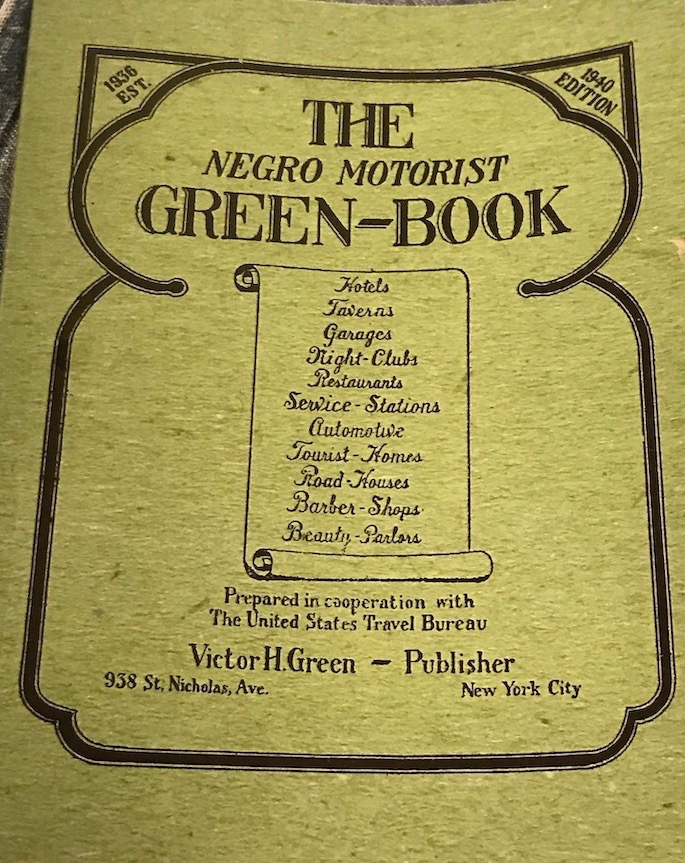

Dr. Wells proudly named his building “The Wells’Built Hotel.” Its upstairs rooms were a haven for black travelers who, by law, couldn’t stay in white hotels or eat in white restaurants. They found it by word of mouth, and by its listing in “The Negro Motorist Green-Book.”

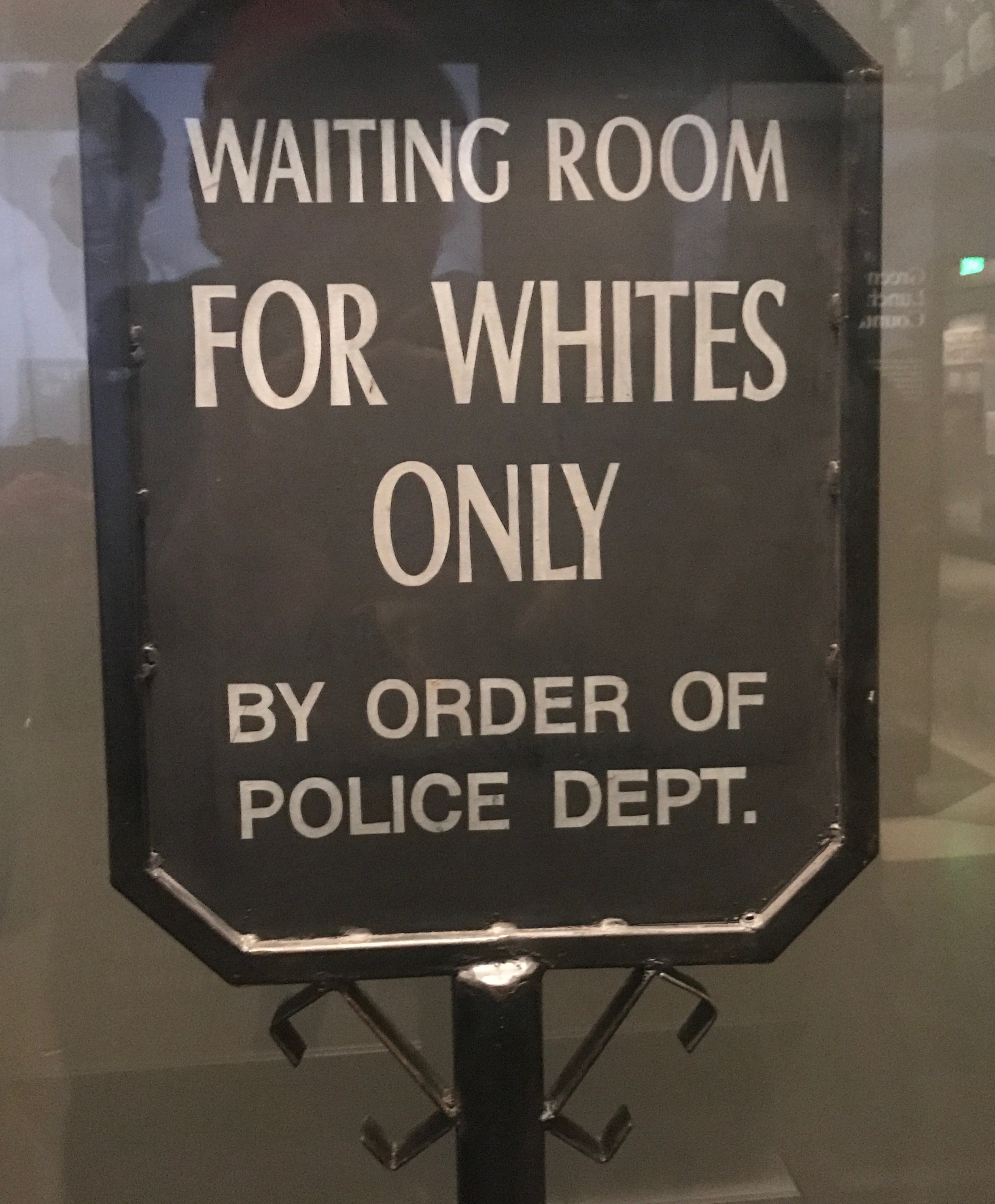

Right up to the 1960s, travel in the South was dangerous and humiliating for African Americans. They were forced to the back of the bus and the “colored” waiting room; barred from the white bathrooms and sent to the outhouse instead. They were pulled over by police or run off the road if their cars seemed too nice to be driven by black people. The Green Book directed them to businesses where they would be served and respected.

The Green Book provided the title of a recent movie that tells the story of a 1962 trip across the South by a distinguished African American pianist, Don Shirley, and his Italian-American driver/bodyguard, Tony “Lip” Vallelonga. It’s a feel-good movie with great performances from Mahershala Ali and Viggo Mortensen as the odd couple who bridge the gaps of race and class to find friendship on the road.

The movie, winner of two Golden Globes and nominated for a handful of Oscars, has been criticized as historically inaccurate. The complaints come mostly from Shirley’s family members, who find some details in the script, and some elements of Ali’s performance, don’t ring true. But that’s a matter of the filmmakers taking literary license, not historical liberties.

More important is what the movie gets right about America before the Civil Rights revolution. Under the Jim Crow laws enacted by state and city legislatures, everything was separate and decidedly unequal. Jim Crow laws were designed to ensure white people and black people never interacted, even casually.

“It was against the law for a colored person and a white person to play checkers together in Birmingham,” Isabel Wilkerson writes in “The Warmth of Other Suns,” her history of the Great Migration. “There were white parking spaces and colored parking spaces in the town square in Calhoun City, Mississippi. In one North Carolina courthouse, there was a white Bible and a black Bible to swear to tell the truth on.”

Where the laws left off, customs and expectations took over. Unwritten rules required black people to step off the sidewalk if a white person was coming, to use “sir” and “ma’m” for white people and accept “boy” in return. As Wilkerson reports, the unwritten racist rules migrants found when up North were almost as illogical and oppressive as the Jim Crow laws they left behind. There were hotels in lots of places where the “no vacancy” sign lit up as soon as the desk clerk saw the color of the traveler’s skin.

But when black travelers passed through Orlando, there was room at the Wells’Built. Its register included the well-off, like civil rights pioneer Thurgood Marshall and Jackie Robinson, who played baseball at Tinker Field. It was a home away from home for the musicians who performed at the South Street Casino next door, a regular stop on what became known as the Chitlin’ Circuit, including Ella Fitzgerald, Ray Charles, Bo Diddley, Louis Armstrong and B.B. King.

The South Street Casino burned down in 1980. The Wells’Built Hotel was saved from the wrecking ball with help from a state senator with an interest in local history. It now houses a modest museum of African American history. One of the rooms upstairs has been restored to its original appearance.

“I can almost see Ray Charles hanging out in here,” I told the museum guide.

“No,” she said. “Ray Charles always stayed over in that room at the top of the stairs. They always kept the furniture arrangement the same so he could find his way around it.”

It’s good that travelers no longer need Green Book hotels. It’s also good to remember places like the Wells’Built not just for the injustice that made them necessary, but for the communities they helped sustain.

Rick Holmes can be reached at rick@rickholmes.net. You can follow his journey at www.rickholmes.net. Like him on Facebook at Holmes & Co, and follow him on Twitter @HolmesAndCo.